As a millennial who is mostly grossed out by fiction and short-format content, YouTube is one of the most important parts of the internet for me.

If all of the streaming platforms were shut down tomorrow I’d be perfectly fine with that. I could even accept a world without social media—though all those meme accounts dissapearing would be a loss for culture. But I cannot imagine an internet without YouTube.

Something about deep dives and click-baity video essays that just fills my void. This need for niche and random knowledge that can’t get met anywhere else, or at least not in a way that feels that in-depth but entertaining.

But it’s not only about video length or browsability, content diversity is also a big part of YouTube’s greatness. I can nostalgia-watch Degrassi: The Next Generation but also go hard on the Ozempic epidemic or any other niche-but-trending subject that I feel like uselessly researching. YouTube is also the official place for music videos (though not longer the only one), an artifact that for an MTV-fed generation like mine is very important to understanding culture and aesthetics.

So I’d been wanting to read ‘Like, Comment, Subscribe: Inside YouTube’s Chaotic Rise to World Domination’ by tech journalist Mark Bergen for a while. Which is an impressively detailed account of the platform from its conception in 2005 to post-pandemic 2022. And a bulky and demanding book, but that’s all right because it documents an important chunk of the history of tech and media.

Here’s some trivia and thoughts that came up while at it.

YouTube is Google

The platform was acquired by Google early on its success. Most people don’t know it because brandwise it has always been kept as a different entity, but YouTube is literally parented by Google, as in all major decisions regarding YouTube are made by Google.

Google tried back in the day with Google Video but it flopped. So acquiring the then emerging YouTube was a huge move that saved the company’s video strategy. It benefited both: YouTube’s longevity as a platform probably has a lot to do with being under Google infrastrucure since 2006.

YouTube didn’t have a clear purpose from the beginning

Vision. Strategy. Roadmap. Big product words. Hard to imagine even small startups could dare to exist with some clarity on them today, but YouTube founders were confused about what they wanted the site to be.

Their idea was vague: they just wanted to make a video website —in part because they had the means for it. One of the initial pseudo-visions was for YouTube to be a video dating site, inspired by the success of Hot or Not. Another one was for it to be ‘like Flickr but for videos’, aimed at creators and inspired by Yahoo’s multimillion-dollar acquisition of Flickr.

They launched without settling on a clear purpose. Clearer strategies came later, but funny how early YouTube’s non-vision is precisely what the platform has been all along: just the video site of the internet.

YouTube’s founders tried to populate the site publishing an ad in Craigslist: “If you are a female or an extremely creative male between the ages of 18 to 45 and if you have a digital camera that can create short video clips, please follow these steps to earn $20.” A bit sexist even for 2005.

An interoperability decision was part of what made YouTube successful early on

YouTube early success was defined by their decision to make their videos embeddable on other sites, unlike competitors at the time. This seemingly simple move made YouTube videos popular on Myspace, helping it emerge as the winner of the online video race in the mid-00s.

This sounds like a really basic version of interoperability today but goes to show its power. Especially now with all the talk around the fediverse and the TikTok ban in the US. Products and content shouldn’t exist in a vacuum and that calls for broader visions of interoperability and ownership that challenge how most platforms operate.

AI was already taking jobs many years ago

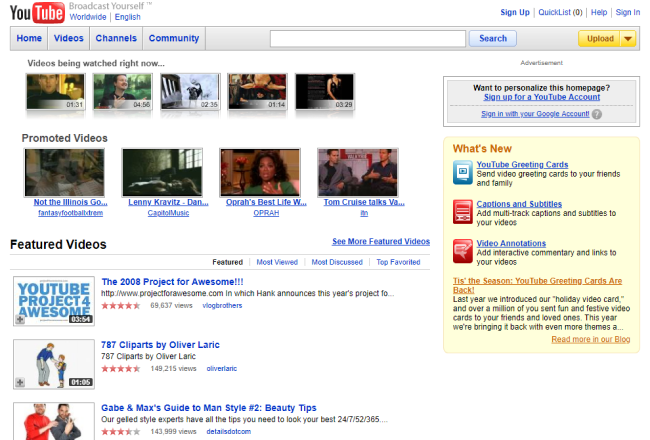

Before its binge-inducing algorithms, YouTube had editors or coolhunters who curated what to feature in the homepage and its categories.

Around 2012 their job started to be taken over by AI and machine learning, as it ‘wasn’t scalable’ and the then human-curated homepage wasn’t performing that well: users were going to the searchbar to discover content instead. So personalized recommendations by advanced algorithms came and, for better or for worse, changed all of that.

Editors slowly became less and less relevant but didn’t go jobless. Some were moved to the marketing department, and some to the YouTube Trends unit which analyzed emerging fads across the site.

In case you forgot how the human-curated homepage looked like in 2008.

Working in tech feels a lot like politics

I’ve had this suspicion from my own experience but this book confirmed it a bit. Working in tech can demand complex soft skills to navigate politics. Many of the situations in the book will feel familiar to anyone that has worked in large or mid-sized organizations.

The tales in it about the late Susan Wojcicki are the accounts of a tech politician. Of course this is truer for C-suites, but it happens at many levels. Even as a designer work can be as much about hard skills as being good at managing complex interpersonal dynamics and systems.

For platforms where people put their work in or depend their livelihood on, product decisions have an impact that go beyond business. And that’s also why governing a product can feel like small-scale politics.

In the book Wojcicki is described as an uncharismatic leader by a former coleague: “But to her credit, that’s not a bad thing at all. Especially in her role, I think a charismatic leader of YouTube might be a disaster. Charismatic leaders kill these businesses because it’s all about them.”

Content moderation is a struggle for platforms

We know the endless stream of content is a struggle for us as consumers. But content is also a struggle for platforms to moderate.

What gets uploaded to open platforms is very difficult to control even with a combo of human teams plus specialized artificial intelligence. The most dramatic episodes on the book revolve around the many controversies and hardships the company had to get moderation right.

Making the norms of what should and shouldn’t be allowed on such a massive platform as YouTube has major ethical, philosophical, and even political implications, for which the company was unprepared. Massiveness doesn’t come without burdens.

Let’s consider the idea of positive radicalization

Much has been said of how media platforms can be dangerous vehicles of radicalization. The book goes all deep on how YouTube, like Facebook in its day, was just that for individuals that commited terrorist crimes.

But could these platforms also foster a softer, beneficial form of radicalization? And this question comes entirely from personal experience. I grew into my veganism and learned a lot about nutrition thanks to niche YouTube plant-based content, which I look back as a good thing.

YouTube also played a role in my coming out during a time I was severely alienated. It gave me a push into my queerness with the It Gets Better Project videos and all the other lesbian, gay and trans real life experiences I found on it. Which, depending on who you ask to, could have been considered radicalization.

***

YouTube isn’t perfect and like most media platforms of the platform age it has been subjected to some degree of enshittification. It has suffered from tiktokfication as well, which I hate, but I’m willing to avoid YouTube Shorts as long as I can.

But judging by its longevity and my recent retirement from Instagram, it’ll likely remain one of my favorite places on the internet.