While not exactly a new idea, digital twins remain a bit of an obscure thing in tech. Maybe because it’s a complex, engineerey topic with lots of disperse promises in different fields.

Digital twins are often defined as a technology, but are more of a concept, really. A concept that can indeed merge many current technologies and is grand enough to hold them all for something larger.

If you look for the definition online, you get a thousand variations, and would probably notice a lack of absolute consensus on what they are. I tried to get to the core of it with the following:

A digital twin is a virtual replica of a physical entity or system

But this definition falls flat. If a digital twin is what sounds like a 3D model of something, why am I even writing this? So we need a more advanced definition:

A digital twin is a dynamic virtual copy of a physical entity or system that looks and behaves like it’s real-world counterpart.

It’s clear then that digital twins are not just static 3D representations. Those can be part of them of course, but what they actually are is living, digital replicas of physical assets. They can integrate information, ingest data, and replicate processes.

Some examples from industrial design

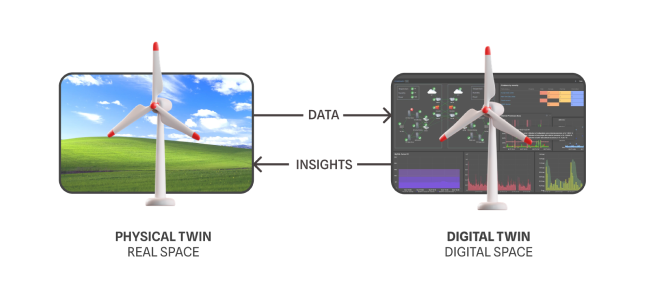

Digital twins were born in the engineering and industrial sector, so let’s draw a classic and boring example from it: a wind turbine. Imagine this white, slick, state-of-the-art, boring turbine has many sensors that are constantly producing data about its performance.

Now imagine this real-world data is being applied in real time to a virtual twin of this particular turbine. Then imagine this virtual twin is a digital space used for simulation and analysis, generating insights that can be then applied back to its physical counterpart, creating a powerful performance improvement loop.

So that’s more or less what a digital twin is and does.

But the general concensus on its definition can get muddy: theoretically, we could also have twins for things that have not yet materialized. And here is where the line between a prototype and a digital twin gets very blurry.

A good, not-so-new example of this is Volvo using Unity to make very comprehensive twins of their in-development models. Should be they considered twins or just highly advanced prototypes? That’s a valid question. The Volvo example goes well beyond what’s traditionally understood as a CAD model, as complex environmental simulations can be run on it and amalgamates information around it in an experiential way, impossible to achieve through regular 3D files or visualizations.

But hang on because it gets more complicated. Digital twins can go beyond objects to replicate complex processes. This product called Moicon allows to create twins of factory lines to optimize operations in what looks like a videogame. So the concept can even stretch itself to mirror more abstract stuff.

But there are levels to them

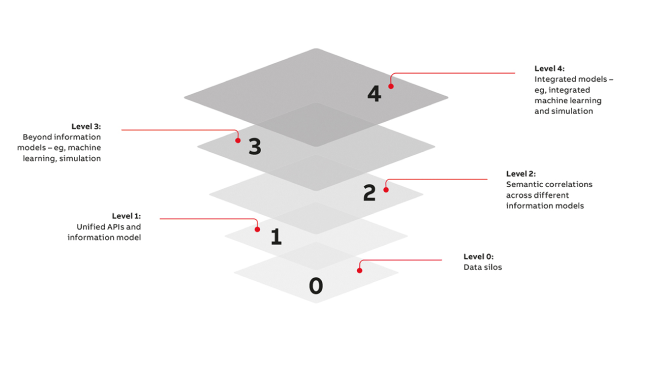

Use cases for digital twins are endless, but on average they are conceived for monitoring, prediction, simulation, and the reuniting of siloed information. The requirements for something to be considered a twin are not crystal clear, but some have established a classification by levels of maturity that works perfectly to understand their possibilities, and also the expansiveness of the concept.

In this, twins can range from level zero, with the goal of ending silos being this super-charged spec, up to the most advanced level which could include machine learning and advanced simulation. But not all twins need to follow the same maturity roadmap (or even follow one at all) to be considered one.

The first digital twins weren’t even fully digital

The concept officially started in 2002, when researcher Michael Grieves proposed an idea for a product lifecycle management platform that included both a real space and a virtual space, and the spreading of data between the two. Just like the boring example of the wind turbine.

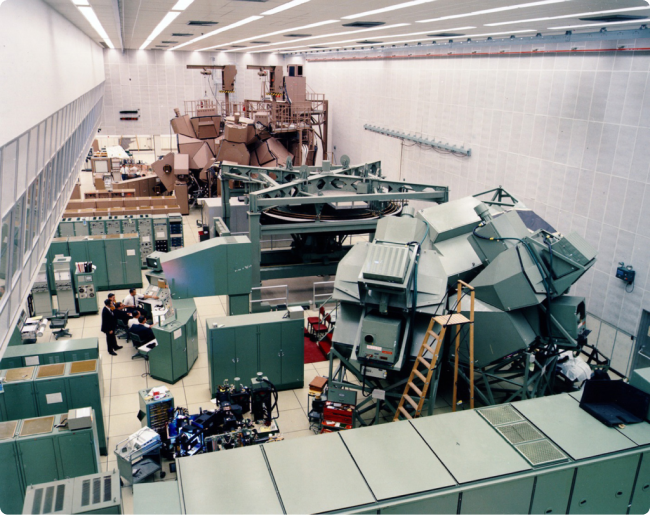

But the application of the idea can be traced back to the sixties, as it was practised by NASA when they duplicated systems at ground level to match aircrafts that were being launched into space. I think they just weren’t called twins by then.

This was what made things like the Apolo 13 rescue mission succeed, because having a twin model allowed engineers to test possible solutions on earth and rescue the crew from space oblivion.

And yes, a physical real-size model might not be digital, but computers were used to simulate conditions onto them. And that makes them the first digital twins, or at least their official ancestor.

Since its official introduction the idea has been growing beyond industrial design, in the form of more enticing visions and applications for architecture, urban development, and even fields that have little to do with engineering, like healthcare and sports.

Digital twins for AEC

Not sure about adoption, but at least aspirationally, the digital twin has gained some traction in the architecture, engineering and construction sector.

It makes sense because AEC could have a lot to gain from them. Improving things like efficiency, decision making and error prevention in an industry like this one means big dollars in savings, basically.

But money aside, digital twins have a lot of relevant use cases here, that span across all of the stages of the building’s lifecycle. Most of these twin products are trying to be marketed as something useful for the entire lifespan of constructed goods, but are inherently meant for specific phases.

Keep in mind these products are still finding themselves, and as they mature – if they even get the chance to do so – they should embrace their strenght. Each stage of AEC is a universe of its own regarding users and needs, so a full lifecycle twin might not even make sense.

Design and construction with digital twins

For design, Unity also has things to offer for AEC. Unity has already profiled itself as a big player in XR, but the same could happen with digital twins. Twins that could leverage XR technology themselves.

Like Unity Reflect, that can be used to preview the building into the real environment and integrate all of the information into a highly-detailed source-of-thruth platform updating in real time. Think of it as a flashier BIM.

For construction – the trickiest phase in AEC – digital twins can take monitoring and progress tracking to new levels. The most interesting products are the ones using reality-capture features to digitize what has been built in a way that allows for remote inspections.

There’s Buildots, which uses a camera to compare the as-built to the as-designed. Or Pix4D, using photogrammetry and drones to scan construction progress and can measure volumes remotely.

Digital twins for the operational stage

But what after a building is live? Turns out this phase is booming with use cases for many users.

Twins for this stage have everything to do with well-known concepts like smart buildings and the IoT. They wouldn’t make much sense for this stage if a building had no sensors and infraestructure to produce data about its usage.

For regular people who go to offices, like me, there’s Haltian. It can tell you the occupancy of the office in real time and a lot more, all with the purpose of improving the experience of working spaces.

They have a feature to know where your coworkers are, which is definitely a bit stalkish, but that I would have totally used when I was working at a macro campus like HP. The product looks immature but they are tackling some valid cases.

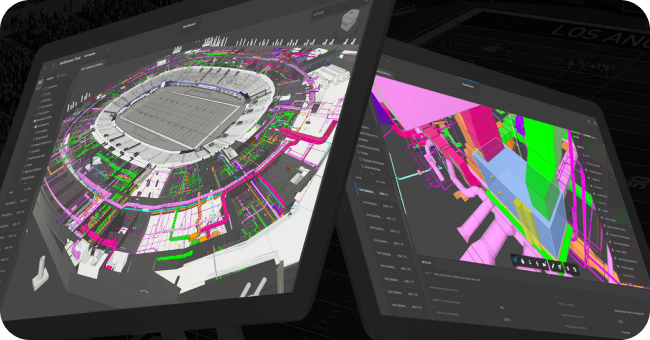

Also, the usage data gathered in a product like Haltian could be useful to building owners and managers. One of the most promising platforms aimed at this segment is Willow, which is used to run the digital twin of the SoFi stadium in LA, allegedly the most tech-forward stadium ever.

Data-driven architecture?

Architects and designers are also a type that could benefit from having twins for the operational stage. They could use data and insights from existing buildings to improve future designs. In fact this is part of the value proposition of Autodesk Tandem, the official twin solution from the CAD juggernaut.

It’s fairly easy to think of data-driven design in tech: what I do as a product designer gets build with lines of code, for example, and usage data is easier and expected to be obtained. But digital twins could make the data-driven approach get widespread in non-digital fields like architecture, as they allow for the datification of physical interactions.

This hypothetical digitization of real environments has greater implications that can go way beyond buildings. It could bring a better understanding of how complex and interrelated systems work to maybe unlock findings that were previously hidden.

But more on that on part two.